<A>

Sangallo (façade, Palazzo Farnese): *

A fortress like 16th-century Florentine palace, representative of a building type reflecting a code of academic rules which exercised immense influence well into the 19th century. The design adhered to classical principles of simplicity, proportion & balance. The inner court is entered through an arch entrance, the carriageway, lined with Roman Doric order antique granite columns. Sangallo borrowed from these from Roman architectural motifs of the Coliseum and the Theatre Marcellus. He was heavily influenced by Alberti & Bramante (with whom he worked). This influence is clear on the frontage where we see Classical orders of columns applied to the 3 levels of the facade. It is Classical as well in its beautiful proportion, somewhat unusual for such a large and luxurious house of the 16th century. Against the smooth pink-washed walls the stone quoins of the corners, the massive rusticated portal and the stately repetition of finely detailed windows give a powerful effect, setting a new standard of elegance in palace-building.

In 1534 Sangallo’s design for the cornice was rejected by Alessandro Farnese. Instead he gave the job to Michelangelo. He increased the overall scope of the building. The building’s 3rd floor was especially reimagined, with its projecting cornice (throwing a deep shadow on the top of the façade). He also added an impressive courtyard. This courtyard, initially designed with open arcades, is ringed by an academic exercise in ascending orders (Doric, Ionic and Corinthian). On the piano nobile (main story) entablature Michelangelo added a frieze with garlands, another Classical feature. He also revised the central window in 1541, adding an impressive architrave to give a central focus to the façade. Above this architrave, he placed the largest papal stemma (coat-of-arms with papal tiara) Rome had ever seen. When Paul III appeared on the balcony, the entire facade became a setting for his person. Indeed these modifications & additions reflect Alessandro Farnese's stellar rise in status: he was elected Pope Paul III in 1534. Michelangelo’s vision & architectural forms represent the growing power of the Farnese Family. The massive palace block & facade now dominated the Piazza Farnese. It was later modified in 1546 by Antonia da Sangallo the Younger. After Sangallo died it was completed by Michelangelo in 1589. The palace as modified clearly is pointing towards the Baroque age, in its secular expressions taking the form of grand palaces, its dramatic content & ornate elements. And clearly Michelangelo is leading the way as far back as the 16th century.

see illustrations below: LEFT the courtyard CENTRE the projecting cornice RIGHT frieze with garlands

SECOND ROW LEFT detail of architrave around balcony

I'm a paragraph. Click here to add your own text and edit me. It's easy.

<B>

Michelangelo (and the Antique): *

While Michelangelo was at the Medici Academy (1490-92) he worked with Bertoldo di Giovanni. Giovanni had been a pupil of Donatello & worked in Donatello's workshop for many years, completing Donatello's unfinished works after his death in 1466. Giovanni was also custodian of the Roman antiquities in Florence. Like his master Donatello, Giovanni drank deeply of humanism. Florence was the centre of this movement which sought to cast off the old ways of thinking in philosophy, religion & art & begin anew. They choose as their “new” model Classical Antiquity because they believed that Greek and Roman art constituted an absolute standard of artistic worth. Michelangelo carved 2 pieces of relief in these years: the Madonna of the Steps & Battle of the Centaurs. The latter was inspired by a classical relief created by Giovanni. This work, The Equestrian Battle in the Ancient Manner, was a recreation of a damaged Roman battle sarcophagus. The subject, battle of Centaurs, had been suggested to the 17 year old Michelangelo by the classical scholar and poet Poliziano. Clearly from an early age Michelangelo was encouraged to seek inspiration in the Classical artefacts which Italy possessed in abundance.

Age 21 he went to Rome. That year, 1496, the city began an exhibition of the newly unearthed sculptures & ruins. The classical sculptures, nude & Herculean in proportion, celebrated the ideals of moral virtue, physical beauty, and truth. His appetite for Classical beauty grew. A decade later (1506) he is called to the site where the Laocoön group was discovered. It was purchased by Julius II and as a special friend of the pope, Michelangelo had unparalleled access to the Hellenistic sculpture. He was particularly impressed by the massive scale of the work and its sensuous Hellenistic aesthetic, particularly its depiction of the male figures.

The Belvedere Torso (see ILLUSTRATION LEFT) is another Classical artefact which influenced Michelangelo. This fragment was a Roman copy (dating from the 1st century BC or AD) of a Greek original dated to the early 2nd century BC, & was known to be in Rome from the 1430s. Michelangelo's admiration of the Torso was widely recognized in his lifetime, to the extent that the Torso gained the sobriquet, "The School of Michelangelo". Pope Julius II purportedly asked Michelangelo complete the fragment with arms, legs and a face. The sculptor declined, stating that it was too beautiful to be altered. It would serve as the inspiration for figures in the Sistine Chapel, including the Sibyls and Prophets bordering the ceiling, several of the ignudi and the figure of Haman; it is also evident in the risen Christ of the Last Judgement. The influence of both the Torso and the Laoccon is reflected in sculptures as well, notably the Rebellious Slave & the Dying Slave, created for the tomb of Pope Julius II.

<C>

Michelangelo (and Counter Reformation): *

Italian architecture of the 16th century followed Classical shape & form. Consequently Renaissance architecture was structured with special attention paid to symmetry, harmony, proportion & geometry. It employed columns & often adhered to the 'central plan' layout emphasising symmetry & order of structures. Michelangelo rejected these restrictions. His interest in light, shadow & space gave him a different perspective & allowed him to see his designs not just holistically but also in terms of living spaces. His work broke down the divisions between structure & decorative detail, allowing greater freedom in design. Sometimes he lowered ceilings to bring more light into rooms, at other times he changed the proportions of details in order to excite a response from his audience. His Laurentian Library (1523) in Florence is a pioneering building in a new style, Mannerist. The Renaissance ideal of harmony gives way to freer and more imaginative rhythms. Even more revolutionary was his ovoid dome for St Peters, a premonition of the future.

Laurentian Library.

The Vestibule’s main feature is its verticality: the walls are divided into 3 sections decorated by double columns, scroll-shaped corbels, and gabled niches framed by pilasters that taper downward in an usual fashion. This dynamism, concentrated on the walls of the vestibule, downflows in the fantastical staircase (built by Ammannati in 1559, following a clay model prepared by Michelangelo). Michelangelo intended the Vestibule to be a dark prelude to the brightness of the Reading Room. The Reading Room, which unlike the Vestibule develops horizontally, hosts two series of wooden benches, the so-called plutei, which functioned as lecterns, as well as book shelves. The vertical tensions of the vestibule seem to quiet down in the long hall of the big Reading Room. Here the guiding principle of the design is the maximum use made of the lateral sources of light.

illustrations below: LEFT- the Vestibule CENTRE LEFT staircase CENTRE RIGHT Reading Room RIGHT exterior view of library

ovoid dome of St Peters.

Michelangelo redesigned the dome in 1547; it shows the building being sculptured, unified and "pulled together" by the encircling band of the deep cornice; this idea was clearly Michelangelo’s concept. The dome must appear to thrust upwards because of the apparent pressure created by flattening the building's angles and restraining its projections. It is not just a structural solution for the tallest dome in the world, it is part of the integrated design solution that is about visual tension and compression. It abandons much of the Classicism of the Renaissance, and more than any other 16th century building, prefigures the architecture of the Baroque.

<D>

pseudo-Corinthian column 15th century versus Roman columns: *

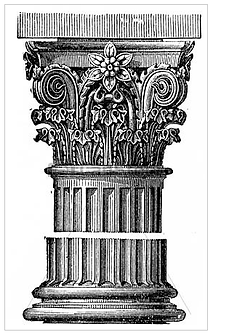

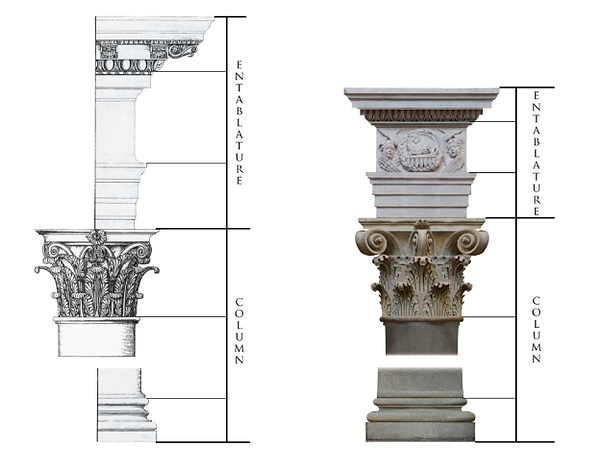

The Romans developed the Corinthian order. A good example is the Temple of Vesta, Tivoli (first century BC). The ambulacrum is surrounded by a cella with 18 Corinthian columns. The capitals have 2 rows of acanthus leaves, its abacus is decorated with oversize fleurons in the form of hibiscus flowers with pronounced spiral pistils, the column flutes have flat tops. The frieze exhibits fruit swags suspended between bucrania. Above each swag is a rosette. The cornice does not have modillions. SEE ILLUSTRATIONS be;low

Brunelleschi was a founding father of Renaissance architecture. Between 1422-1428 he built the Old Sacristy of the Medici Chapel (in the Basilica of San Lorenzo), Florence, a building which illustrates the transition between Gothic & Renaissance. Brunelleschi probably knew at least part of De Architectura (written 30-15 BC by Vitruvius) & also observed ancient ruins in Rome. His architecture is a ‘hybrid’ language containing elements of Florentine vernacular architecture, Romanesque, Gothic & classical. From this milieu, Brunelleschi developed a hybrid Corinthian style. The architectural order is clearly Corinthian as reflected in the style of the capital which has leaves and helices & a continuous frieze in the entablature. The proportions are also those of the classical tradition. However we also see Gothic & Florentine influences. The entablature, although divided into the 3 canonical elements (architrave, frieze & cornice) shows proportional & morphological differences from the Vitruvian canon. The latter used an equally tall frieze & architrave with a taller cornice; with Brunelleschi’s Corinthian however, the frieze is the more prominent element, with a similarly tall architrave & a much shorter cornice, around half of the other 2 elements. These proportions echo those of Romanesque architecture in Florence (e.g. Baptistery of Saint John). In addition, the capitals reflect influence from the late-medieval capitals of Florence, despite maintaining all the essential elements. The tiers of leaves are reduced from 3 (Classical Corinthian) to 2; they are oak leaves NOT acanthus leaves (a legacy of the late-medieval Florentine capitals). The Brunelleschi volutes, instead of using the usual helices, employ 8 plastically protruded volutes (chioccioli, a reference to the shells of nails). Dimensionally these capitals are 1 module tall (as prescribed by Vitruvius). However the ratio with the now shorter entablature gives them greater importance, whereas in antiquity they were considered equally relevant in the architectural order. Brunelleschi’s also omitted the pedestal (1 of the 3 parts of the classical order). This ‘new’ architecture became popular & major Florentine painters celebrated it by reproducing it in their paintings (e.g. the Corinthian capitals in Masaccio’s Holy Trinity)

SEE ILLUSTRTIONS BELOW

LEFT: Corinthian Order according to Vitruvius RIGHT Corinthian Order AT San Lorenzo

<E>

Michelangelo (Sistine chapel fresco capturing Apollonian Soul): *

In particular the Ignudi, the 20 athletic nude males, supporting figures at each corner of the 5 smaller narrative scenes running along the centre of the ceiling. Although all seated, they are less physically constrained than the Ancestors of Christ. Their posture are similar but with variation & the variations become greater with each pair until the postures of the final 4 bear no relation to each other whatsoever. Their meaning is obscure but is in keeping with the Humanist acceptance of the classical Greek view that "the man is the measure of all things"; they clearly reflect classical antiquity.