<A>

Andrea Mantegna): *

His rendering of the human body reflects his knowledge of relief sculpture of antiquity. His flinty, metallic landscapes & stony figures reflects a fundamentally sculptural approach to painting. His teacher, Squarcione, endowed Mantegna with a love for antiquity; he studied reproduced castings of antique sculptures at Squarcione's Studio. He was also influenced by Donatello, another student of Classical sculpture. When Mantegna was in Rome (1488 to 1490) he spent time to study the sculptural masterpieces there. Trained in the study of marbles & the severity of the antique, he claimed ancient art superior to nature being more eclectic in form. He worked to exercise precision in outline, privileging the figure. His figures tends towards rigidity, demonstrating an austere wholeness rather than graceful sensitivity of expression. Draperies are tight & closely folded, taken from models draped in paper and woven fabrics gummed in place. His figures are slim, muscular and bony; the action impetuous but of arrested energy.

see image below

The Assumption and the Martyrdom of Saint Christopher.

Mantegna was 1 of several painters entrusted with decorating the Ovetari Chapel in the Church of the Eremitani in Padova. This image was part of his

cycle depicting the Martyrdom of San Christopher (1448 to 1457).

<B>

Signorelli: *

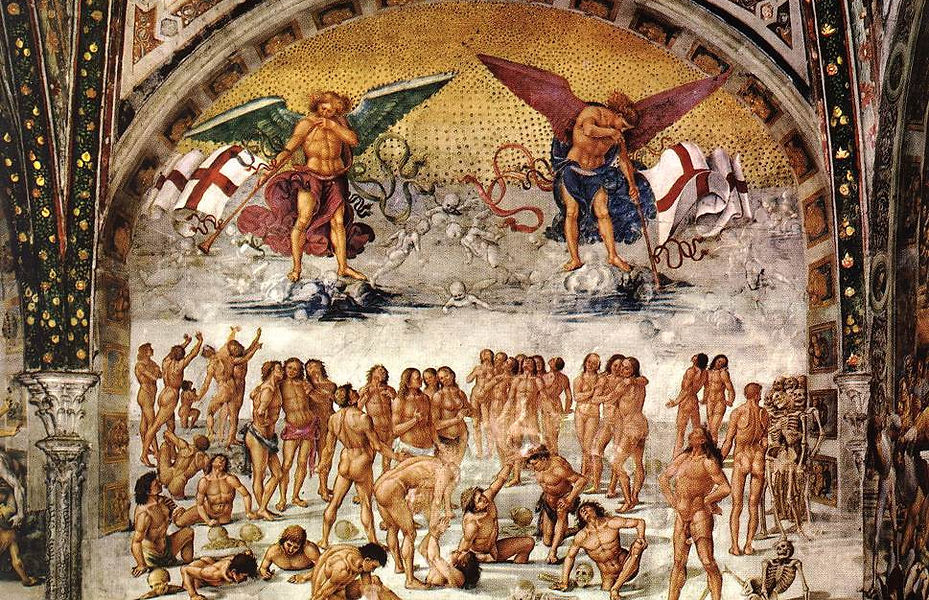

LEFT: Resurrection of the Flesh (1499-1502) Fresco Chapel of San Brizio, Duomo, Orvieto. Signorelli

ROGHT: The Last Judgement (1535-41) Fresco Sistine Chapel Rome, Michelangelo

<C>

Leonardo: *

the Annunciation (1472–1475) oil & tempera on panel

a very traditional subject & composition, popular & used many times in Florentine art (Fra Angelico). Ye within this tradition constraint Leonardo produces a free, imaginative composition where infinite relationships arise within the painting, and between the main subject& the surrounding space. The linear perspective acts as a controlling factor while encompassing the whole composition within its close network of axes & co-ordinates, all of which come together in the little mound alongside the wall on the right-hand side of the painting.

.jpg)

LEFT: At the same time, we see the use of atmospheric perspective in the background, employing effective sfumato, showing us a vista in distant space.

RIGHT: Each episode has an autonomous existence. The gesture of the Madonna, as she sits framed by the jutting wing of the building, coincides with the reflection made by the falling light upon the stone, while the close-knit perspective network of the bosom, the controlled movement of the interposed suspended gesture, and the withdrawal of the head, become fleeting signals of emotion.

<D>

Rubens: *

LEFT: Venus Before The Mirror (1615)

A common theme in the Renaissance & Baroque eras (notably Titian); Rubens reinterprets the theme in line with the Flemish Baroque spirit; his Venus is more human than Titian's. Her figure fuller, more curvaceous, with hair that cascades down her back, and instead of gazing at her own beauty she catches the eye of the viewer.

RIGHT: Hercules as Heroic Virtue Overcoming Discord (1632 -1633)

Oil on pane, one of many preliminary models for the ceiling of the Banqueting Hall, Whitehall London; commissioned by Charles I, it is 1 of 4 corner ovals depicting Virtue's triumph over Vice in allegorical form & may refer to Charles I's political ambitions.

<E>

Palladio (lead to nothing): *

IMAGE Villa Rotunda

Its design is completely symmetrical with a square plan, 4 facades, each with a projecting portico; the whole is contained within an imaginary circle touching each corner of the building & centres of the porticos. It reflects the humanist values of Renaissance architecture. Each portico flanked by a single window & has pediments adorned with statues of classical deities, their pediments supported by 6 Ionic columns. Building began in 1567; with Palladio’s death (1580) the work was completed by Vincenzo Scamozzi in 1592.

Spengler judges Palladio “to lead to nothing” because the succeeding style, the Baroque, abandoned much of the Greco-Roman feel. Renaissance architecture (including Palladio) was noted for its clean lines, symmetry & proportion using Greco-Roman elements (columns, pilasters, lintels). An understanding of perspective led to more conscious composition of architectural form. Its balance & symmetry appealed to the intellect. In contrast Baroque is emotional, appealing to the widest audience. It uses dramatic lighting & colour, the line replaced by curves and twists. The plain marble finish of the Renaissance surface is replaced with a richer surface treatment, gilded statuary & bright colours. It uses dynamic designs & complex architectural plans to heighten feelings of motion & sensuality, using on the oval (not the square or circle). Renaissance classical motifs are used but often broken up or distorted. It employed illusory effects (trompe l’oeil), with designs that played games with architectural features, sometimes leaving them incomplete. Many features )central towers & domes) are European not Greco-Roman; new motifs included the cartouche, trophies & weapons, baskets of fruit or flowers, none especially Greco-Roman. Although aspects of Renaissance buildings were retained, the classical repertoire is now crowded, dense, overlapping, loaded, in order to provoke shock effects.

Palladio did have an impact. He inspired architects in France & Germany, notably Ledoux in France, as seen in the Royal Saltworks at Arc-et-Senans (1775). The German architects D Gilly & F. Gilly admired Palladio & constructed palaces for the German Emperor Frederick-William III in this style (Paretz Palace, 1795-1804). Palladio was especially popular in England, where the villa style was adapted for country houses. Palladio also appealed to the USA where the architecture & symbols of the Roman Republic were adapted for monuments in the new nation’s capital. Palladio inspired Monticello (1772), the residence of Jefferson. However, Spengler would point out that much of his influence was only really evident in the mid 18th century, long after his death.

BELOW: Chiswick House London, England by Richard Boyle, 3rd Earl of Burlington and William Kent (completed 1729);