6.

force and mass: *

The pointed arch visible in windows, doorways & arcading between supporting columns was major departure from the Romanesque semi-circular arch. The latter was limited as the height of the arch was always exactly half its width. In contrast the pointed arch allowed any ratio of height to width (thereby allowing naves to be built higher). Structurally it had great advantages; a greater proportion of the weight (mass) above the arch is channelled down into the ground, instead of exerting a sideways force. Ribbed vaults replaced the heavy semi-cylindrical barrel vaults which limited the size of the building. The new style employed a web of ribs (intersecting stone arches) to provide strength; the space between the ribs (which was not load bearing), could be filled with lighter stonework. The ribs channelled the mass (load) down through a column to the ground. Such a system allowed the mason to build higher. A buttress is a heavy pillar of stone built up against an outside wall to counter thrust (the weight of masonry pushing sideways on the wall). This assumes, however, that the wall extends vertically all the way to the ground. In many Gothic buildings this was not the case, because the upper tier was narrower than the lower tier. The supporting pillar for the upper part of the wall had to be sited a distance away from the lower wall, and connected to it by a load-bearing arch. The resulting combination of pillar and arch is called a flying buttress.

see illustration of Amiens cathedral (built between 1220-1270)

7.

Classical and Western tragedy: *

Classical tragedy.

background-- a religious phenomenon, associated with a religious festival & a polis (Athens).

structure-- the theatre was circular with an orchestra and often an alter in the middle (emphasizing the essential religious nature of the drama). Greek tragedies were staged outdoors and during the day. The actors wore masks and were limited in number: the chorus, protagonist and often only one other (allowing a dialogue with the protagonist). Aristotle refers to the 3 unities (action, place, time) allowing the play to be a whole, a unity.

content-- the plays are meant to honour the Gods. In Oedipus Rex Sophocles infers that no man can outsmart the Gods or avoid the fate the Gods have decided; it is an act of hubris to attempt such. Aristotle characterises tragedy as the downfall of a basically good person through some fatal error or misjudgement. This is the tragic hero (protagonist) who inadvertently causes suffering but who receives insight. His fate arouses pity & fear in the audience.

Western tragedy.

background--Shakespeare’s theatre was a business venture and had nothing to do with religion or the Church. It was secular.

structure--plays were performed indoors, day or night. There is no chorus in Shakespeare and he used many more actors on stage, none with masks.

content--his plays have no religious connotation or tradition but are secular. His plots do not suggest a preordained ending but allow human agency. It is the hero’s free will rather than fate which will lead to tragedy. In Hamlet it is the protagonist’s procrastination which leads to the tragic ending, not Fate. We also see Good versus Evil in Shakespeare. In his tragedies Goodness never beats Evil because the evil element is always disguised, while goodness is open and freely visible to all. Shakespeare paints evil as an indispensable & ever-enduring thing.

8.

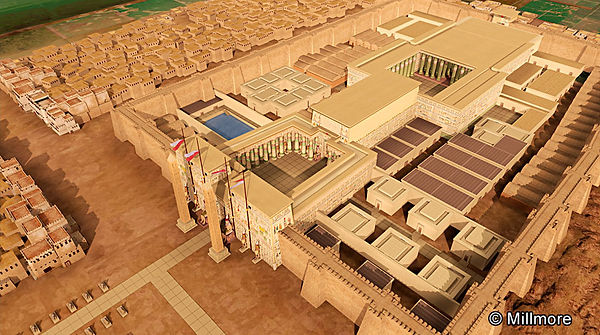

Egyptian (serial arrangement of statues, sphinxes, temple halls): *

An avenue of human headed sphinxes over 1.5 miles long connected the temples of Karnak and Luxor; used once a year during the Opet festival when the Egyptians paraded along it carrying the statues of Amun and Mut in a symbolic re-enactment of their marriage. At Luxor temple Amun was magically transformed into Min the god of fertility. Around 1,350 sphinx statues are thought to have lined this road.

Luxor temple of Rameses II displays a strong rectilinear feeling (forming a straight line).

9.

arabesque over Early Christian picture: *

A conspicuous feature of art in the Islamic world is the limited use of naturalistic images of living beings. Islam, like Judaism and in certain periods Byzantine Christianity, prohibited the making of images. The purpose of this prohibition was initially to avoid idolatry as Muhammad himself demonstrated when he purified the Kaaba of sculptures and idols. It was an important aspect of the new doctrine that no one should be induced to worship an object or an image instead of God. The Koran provides no specific guidelines for the use of images. The hadith (the traditions of the words and deeds of Muhammad) express a clear antipathy towards figurative depictions. Some hadiths make it absolutely clear that a person who tries to emulate God’s creative force will be hard pressed on the Day of Judgment. As a consequence of the prohibition of images, the non-figurative character of religious decoration has remained a fundamental principle throughout the history of Islam. Images are never found in mosques nor is the Koran illustrated with depictions of Muhammad. With the reform of coinage in 696 AD even the portraits of rulers were removed from Islamic coins and replaced by calligraphic decoration. The result of constraints in the use of figurative depictions led Muslim artists to concentrate on abstract forms of expression. In traditional Islamic art, vegetal ornamentation, geometric patterns, and a fascination with script (calligraphy) reached unprecedented heights.

10.

oil painting (retreat of): *

Brilliant beginnings

Oil did not gain popularity until the 15th century; frescoes and tempera dominated prior to this. The transition began with Early Dutch painting in the 15th century (Northern Renaissance). Improvement in oil paint & techniques by Dutch artists like Jan van Eyck led to its adoption in Italy, first in Venice in the late 15th century & it quickly spread. By 1540, tempera was abandoned; by the height of the Renaissance oil painting had replaced all earlier techniques. Oil lent itself to the depiction of tonal variations & texture, facilitating the observation of nature in detail.

Along with oil, the geniuses of the Renaissance (1400-1600) transformed the visual arts, developing optical techniques providing greater realism & perspective. In the 14th century they developed proportion, treating the painting as a window into space; in 1415 Brunelleschi developed true linear perspective. They used foreshortening, shortening lines in a drawing to create depth. They used sfumato, blurring sharp outlines by subtle, gradual blending of one tone into another, giving the illusion of depth. Finally chiaroscuro (modelling) employed strong contrasts between light and dark, adding to the depth illusion. Leonardo da Vinci (1452-1519) was the artist who perfected these trends (lighting, linear & atmospheric perspective, anatomy, foreshortening & characterisation). Oil paint was his primary media, allowing him to depict light & its effects on the landscape & objects more naturally, with greater dramatic.

The Baroque period (1600-1750) focused on the drama of their subjects, the inner emotions & conflict. They used Renaissance foundations (perspective, realism, vivid evocative pigments, primary colours) but instead of calm balance sought drama and tension, both in emotion as well as physical states (at rest versus straining, twisting & turning). The genius of artists like Caravaggio & Rembrandt were the equal of Leonardo, Michelangelo and Titian, their Renaissance peers!

The Baroque was followed by Neoclassical (1750–1850), backward looking trying to recapture Greco-Roman grace & grandeur; later Romanticism (1780–1850). Neither of these are considered to be the greatest ages of Western painting.

11.

chamber music:

Medieval music (1000-1400) is the starting point in Western music; it had yet to acquire true monumentality. In the Middle Ages & early Renaissance instruments were used as accompaniment for singers. Up to 1600 music was dominated by the plainsong liturgical music of the Church, primarily Gregorian chant. Renaissance music began in northern Europe & introduced new forms & included secular variants but like its medieval ancestor, remained undeveloped. Only with the Counter Reformation did the great ascent begin, first with the Baroque period (1600-1750). This age saw the creation of tonality, in which a song was written in a particular key, a principle which has guided Western music to the present. During this period chamber music became a tour de force.

Chamber music, a form of classical music, is composed for a small group of instruments, traditionally a group that could fit in a palace chamber. The origin of classical instrumental ensembles lies in the sonata form, compositions for 1 to 5 instruments. The trio sonatas by Corelli (Opus 1, 1681) were of unparalleled influence during his lifetime & for many years after. However the giant of the sonata form is Bach (1685-1750). In the Baroque period (1600-1750) chamber music remained undefined; works could be played on any variety of instruments, in orchestral or chamber ensembles. Bach’s Art of Fugue can be played on a keyboard instrument, a string quartet or string orchestra. Baroque chamber music was often contrapuntal, each instrument played the same melodic materials at different times, creating a complex, interwoven fabric of sound. Haydn (1732-1809) created the modern form of chamber music writing string quartets, piano & string trios, duos & wind ensembles, the conversational style of composition, a form that would dominate for the next 2 centuries. Mozart (1756-1791) greatly expanded the vocabulary of chamber music, adding numerous masterpieces to its repertoire. His genius brought chamber music fully into the epicentre of Faustian Culture.

Around 1800 major chances impacted chamber music. The eclipse of the aristocracy saw the rise of the middle classes; composers now made money by selling their compositions & performing concerts. New methods of constructing violins, violas & cellos emerged giving these instruments richer tones, greater volume & carrying power. In the late 1700s, the piano became popular as an instrument for performance. Music migrated from the court to the orchestral hall, from the nobility to the middle classes. Beethoven (1770-1827) dominates this period, a giant of Western music; he transformed chamber music, raising it to a new plane with his symphonies. Franz Schubert (1797-1828) would bring chamber music into the new emerging romantic style.

IIn the 1860s a schism grew among romantic musicians over the direction of music. Liszt and Wagner argued that "pure music" had run its course with Beethoven, and that a new, programmatic form of music, in which the composition created "images" with its melodies, was the future of the art. The great age of chamber music was over.